Why butterflies?

Because they are messengers from the insect to the human world. Not because they are here for us, but because they are among the only insects to which we feel any positive response, when we notice them – and most people don’t.

• Roberty Michael Pile, butterfly conservationist

In 1988 I collaborated with Jeff Brown, a landscape architect, on a temporary public art installation using fennel as a major element of the design. Jeff suggested using fennel because it is a non-native invasive plant found everywhere in the bay area, including rocky hills, vacant lots, sidewalks, and old railroad tracks.

One day after our installation, I noticed a big green and black striped caterpillar on a fennel leaf. When I touched the caterpillar, orange horns emerged from its head and a strong aroma of fennel was emitted. This moment brought me back to my childhood in Japan. My parents’ yard had an orange tree that was home to large, beautiful bright green caterpillars. They had artificial eyes on their backs, and when I scared them, orange horns came out of their heads and they too emitted a strong odor. Sometimes I saw large yellow and black swallowtail butterflies near the tree, and every year they would return.

I have been in America since 1981, and did not realize how much I used to love viewing the butterfly cycle until I saw the caterpillar on the fennel leaf. The discovery made me very happy, for I realized that something familiar to me was always nearby; I found myself wanting to be closer to butterflies. I started collecting caterpillars and rearing them. I called the San Francisco Insect Zoo to learn more about the type of butterfly. Its name is anise swallowtail, and the female butterfly is believed to come back to her birthplace to lay her eggs.

My husband Tim and I lived in a place that used to house a community arts center called Crossroads Community/ the Farm. The Farm was on five and a half acres, under and within a freeway system. Even though much of the Farm’s area has been converted to other uses, there are still some surviving plants, including fennel. I was able to find many anise swallowtail caterpillars close to home. In 1988, I was an artist in residence at the Headlands Center for the Arts in Marin, California. I presented two installations, Haru and Natsu, involving the metamorphosis of the anise swallowtail butterfly. An essential component of both of these installations involved the release of the butterflies. I never detained the butterflies in the exhibition space unless they had broken wings or would have had to be released into bad weather.

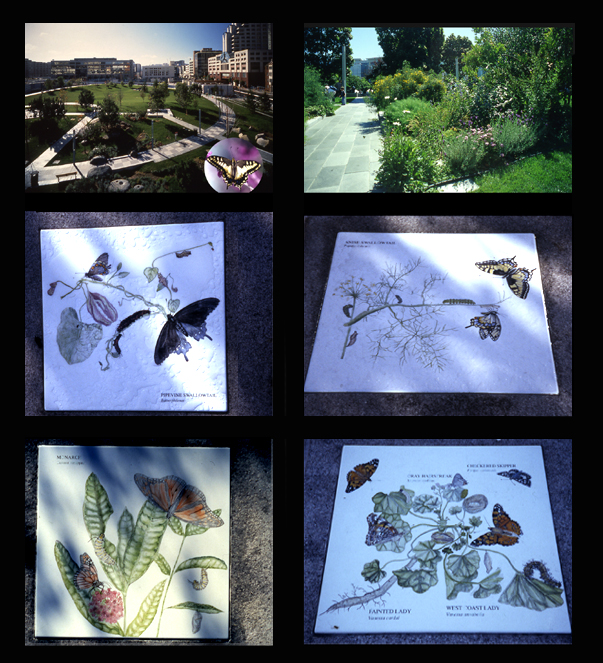

The Yerba Buena Garden Project

In 1991 the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency sought artists to implement a site-response to a garden area of the expanded Moscone Convention Center. One of the initial requests of the artists was to ”contribute to the project’s overall sense of place and to one’s sense of orientation within the place.”

The redevelopment agency became interested in the idea of a butterfly garden after they saw a slide show of mine which include the two Headlands butterfly installations. However, I felt that inviting butterflies into the downtown roof garden would not be an easy job for either the butterflies or myself. I decided that even though the propability of creating a quality habitat experience in the Yerba Buena Gardens Meadow was nearly impossible due to location constraints, I could promote my ideals by introducing the type of plant materials that would nurture insects and animals.

I spent a year submitting different possibilities for the project to the redevelopment agency. During this period, I began an extensive study of local butterflies and their habitat needs. I met Leslie Saul, Director of the San Francisco Insect Zoo, and asked her about common butterflies in San Francisco. She gave me lists of butterflies and their host plants, and also took me to the Nature Trail in Golden Gate Park. There I met Donald Mahoney, Ph.D., who works as a nursery coordinator and Nature Trail supervisor for the Strybing Arboretum. Don suggested my meeting with Barbara Deutsch, who had been rearing butterflies and creating a butterfly garden on a slice of what is left of wild hillside on Portrero Hill. She has been developing her garden, a small trail, since 1984.

I will never forget my first meeting with Barbara. She showed me a few kinds of larva plants that looked like weeds, and explained what kinds of butterflies use them. After returning from Barbara’s house, I found many of these plants and different kinds of caterpillars near my home. They were always near me – I just hadn’t noticed! Leslie, Don and Barbara truly introduced me to the world of butterflies. Their knowledge is based on active experimentation and observation, rather than on books.

I will never forget my first meeting with Barbara. She showed me a few kinds of larva plants that looked like weeds, and explained what kinds of butterflies use them. After returning from Barbara’s house, I found many of these plants and different kinds of caterpillars near my home. They were always near me – I just hadn’t noticed! Leslie, Don and Barbara truly introduced me to the world of butterflies. Their knowledge is based on active experimentation and observation, rather than on books.

Finding the right plants for the garden was not a simple task. Books were of little use, since many of the plants that the butterflies traditionally used have been lost to development. Decreasing the habitat of native plants threatens wildlife, and butterflies are no exception. Some of the species have had to find other food sources: red admiral found pellitory; anise swallowtail use fennel rather than cow parsnip; painted lady, west coast lady, and the gray hair streak use malva.

I felt the garden design needed to be reviewed by an entomologist and a botanist to give it a firm footing in reality. Also there was concern that the concept of the urban reintroduction of butterflies would get lost in the stronger visual element of the garden design. I talked the dilemma over with Barbara, and she offered to help with the project. She also suggested that I work with Leslie and Don before giving my final proposal to the redevelopment agency.

My final proposal for the Yerba Buena Garden involved creating an urban garden for butterflies. The garden provides a convenient and well stocked rest stop for butterflies as they traverse the urban landscape of the Bay Area. To accomplish this, I introduced larva and nectar plants as hosts for the butterflies. In addition, I devised a system to protect the vulnerable larvae, and established a program of nurturing maintenance.

I have developed a maintenance plan to train garden workers in proper butterfly garden care. They need to be aware that the plants and composition of the butterfly garden are in some cases directly at odds with traditional areas in the garden. Many of the larva plants are considered weeds, and their appearance seems somewhat unkempt to those more familiar with the controlled techniques of the classic garden. In addition, the garden workers need to develop an awareness concerning the life cycle of the butterfly, and adapt gardening methods to accommodate the creatures’ habitat. Finding alternatives to pesticides will be an important issue, since herbicides and pesticides will be prohibited in order to protect all life throughout the garden both insect and human. The maintenance plan explores these important issues.

In addition to creating a welcoming environment for butterflies, the garden provides an opportunity for audience awareness and education. Rather than focusing solely on the end product, the garden directs attention toward all aspects of the butterfly life cycle. To further educate the public, four plaques were installed, each illustrating the stages of metamorphosis for a different butterfly species.

The butterfly garden must be viewed as an ongoing project. That is, the site will need to settle in for a year or so, giving the plants time to get established. Following this, continuous study will be neccessary to determine which butterfly species are attracted to the site and how the garden may be adjusted to accommodate their needs.

Recently, while visiting my favorite butterfly garden with a group of grade school teachers, one of the major questions I heard asked was, ”What are we supposed to be looking at?” It is a good question, indicative of our cultural need for immediate gratification, as well as our impatience with all things natural. But the most telling part of the question is the notion of looking at something. Standing away, we see things based on our intellectual and aesthetic training. We compare, contrast, criticize and appreciate a display. I hope this butterfly garden becomes something more, an oddly kept amalgam of weeds and plants, piles of clippings stacked near their source, an obvious sense of unmanicured chaos, which under close inspection is filled with life and purpose. A place where the inquiring mind can search and discover, where careful and present awareness is rewarded by the flash of a caterpillar’s colorful coat or the camouflage of a chrysalis.

By briefly introducing simple concepts like larvae plants and nectar plants, the garden will whet the appetite of the curious. A tour of the undergrowth ”belly down and nose in the dirt”, may nurture a visitor long after he or she has left. The garden is meant to be experienced, not just looked at.

My partners and I envision for the future a wildlife corridor of interconnecting green spaces designed with habitat needs in mind. It will promote the propagation and movement of wild creatures, and encourage awareness of Nature’s wonders, even within the heart of the city.